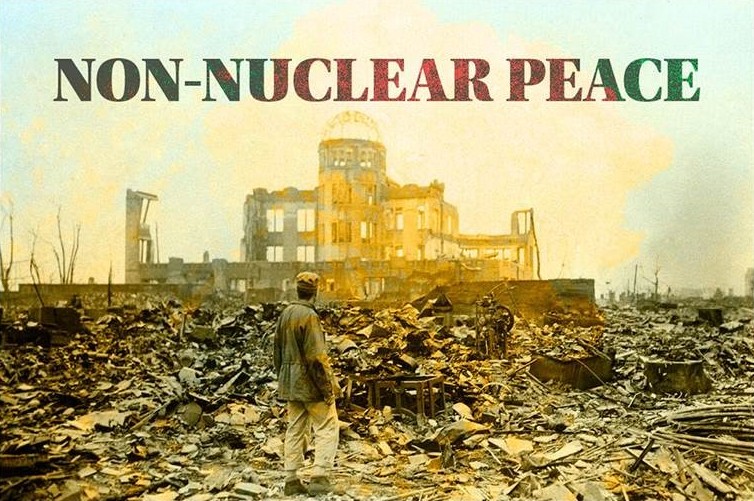

Non-Nuclear Peace

UCSIA organised this public lecture on Non-nuclear peace within a series of academic workshops on different aspects of peace (cf. workshop on pacifism of last December and workshop on peacebuilding next December). Keynote speaker Campbell Craig, Professor of International Politics at the School of Law and Politics of Cardiff University, recently returned from the US where he witnessed a come-back of the nuclear discourse, and the belief that a nuclear war can be won. He shared his ideas on this troubling development with an audience of around 90 attendees, including the 20 researchers involved in the ensuing expert workshop.

Tom Sauer, Head of the Research Group International Politics at the Department of Political Science of the University of Antwerp, and co-organiser of the workshop, introduced the topic of the lecture, by pinpointing the role of information and how it affects the debate on different levels, from academia, over media to public awareness. Academic scholarship is divided on the necessity of nuclear weapons for deterrence versus complete abolishment to guarantee worldwide peace. Many do change position from the former tot the latter, never the inverse. Students generally evolve towards a more sceptic stance throughout their studies. Media information is often biased or non-existent (cf. how little attention they paid to the Ban Treaty). General public opinion is ill-informed and expresses little protest in comparison with the nineties.

Nuclear power exists and sovereign states may use it. Who might oppose it? Not the nuclear establishment working for liberal governments and abiding to official policy, while taking refuge in a managerial approach of the problem. It will have to come from radical opposition, but disagreement on the course to take weakens their stance. To tackle the problem two courses are available: focus on the weapons to have them destroyed or focus on the states who might use them and create a new system. Both courses have their weaknesses; with the former course the hypothesis of new bombs being built is not to be excluded, with the latter, nations willing to surrender power to a world government are rare. Opposition seems unrealistic, but that is why it needs to be radical. A basic change and a new discourse are imperative.

A radical alliance against mainstream establishment requires an understanding of the impact of nuclear weapons on politics (and the recognition that nuclear deterrence does seem to work), an agreement on a political project to counter the nuclear establishment (states and institutions that support research in nuclear strategy in the absence of democratic checks render the world dangerous) and the development of an alternative order not based on coercion (whereas the nuclear establishment prefers to preserve the status quo). It goes further than avoiding a nuclear war, it is about developing a positive vision of change within global politics.

In the ensuing Q&A, following questions were raised:

- Cannot we start from pluralist security communities, such as the EU instead of establishing a world state?

- Cannot we apply the same strategies that led to the ban on biological and chemical weapons?

- Is it not a matter of changing mentalities to create a culture averse to nuclear weapons? Is there not a danger of polarization in the radical approach?

The exchange of ideas continued throughout the workshop of the next two days between the invited experts, such as Patricia LEWIS, Research Director International Security, Chatham House, London, UK, Casper SYLVEST, Associate Professor, Dept. of History, University of Southern Denmark, Nina TANNENWALD, Director of the International Relations Program, Watson Institute, Brown University, USA, Harald MULLER, Professor emeritus of International Relations, Goethe University Frankfurt.

Casper Sylvest highlighted the role of nuclear weapons in intellectual history after 1945 and showed how the nuclear arms race during the Cold War transformed scientific knowledge about the earth and the public role of the scientist and how intellectual concepts and ideas produced by new technologies underpin the stance on nuclear weapons.

Nina Tannenwald sketched the development and evaluated the potential impact of the Humanitarian campaign for a total ban on nuclear weapons. She expects an effect on changing norms in nuclear states through the weapon of stigmatisation, democratisation of the political issue and support for normative dismantlement strategies.

Harald Muller tried to formulate an answer to the question of what institutional framework is needed to guarantee non-nuclear peace. The Ban Treaty may be instrumental in developing the necessary political will (and relax competition between states), strengthening military control and verification, but above all, to encourage the establishment of cultural norms for a mentality change in favour of the nuclear taboo.

These topics were further investigated in panels, where theoretical reflections and empirical case studies were presented from different parts of the world such as Germany, Japan, Australia, Brazil, South-Korea, …

Date

23-25 May 2018

Location

University of Antwerp

Prinsstraat 13

2000 Antwerp

BELGIUM